ON EDGE: In 2008, “as a matter of pride,” Honnold walked across Thank God Ledge, while free-climbing Half Dome in Yosemite. Later, he wrote, “Walking face-out across Thank God Ledge is surprisingly scary.”

Alex Honnold doesn’t experience fear like the rest of us.

BY J.B. MACKINNON

Alex Honnold has his own verb. “To honnold”—usually written as “honnolding”—is to stand in some high, precarious place with your back to the wall, looking straight into the abyss. To face fear, literally.

The verb was inspired by photographs of Honnold in precisely that position on Thank God Ledge, located 1,800 feet off the deck in Yosemite National Park. Honnold side-shuffled across this narrow sill of stone, heels to the wall, toes touching the void, when, in 2008, he became the first rock climber ever to scale the sheer granite face of Half Dome alone and without a rope. Had he lost his balance, he would have fallen for 10 long seconds to his death on the ground far below. One. Two. Three. Four. Five. Six. Seven. Eight. Nine. Ten.

Honnold is history’s greatest ever climber in the free solo style, meaning he ascends without a rope or protective equipment of any kind. Above about 50 feet, any fall would likely be lethal, which means that, on epic days of soloing, he might spend 12 or more hours in the Death Zone. On the hardest parts of some climbing routes, his fingers will have no more contact with the rock than most people have with the touchscreens of their phones, while his toes press down on edges as thin as sticks of gum. Just watching a video of Honnold climbing will trigger some degree of vertigo, heart palpitations, or nausea in most people, and that’s if they can watch them at all. Even Honnold has said that his palms sweat when he watches himself on film.

All of this has made Honnold the most famous climber in the world. He has appeared on the cover of National Geographic, on 60 Minutes, in commercials for Citibank and BMW, and in a trove of viral videos. He might insist that he feels fear (he describes standing on Thank God Ledge as “surprisingly scary”), but he has become a paramount symbol of fearlessness.

He also inspires no shortage of peanut-gallery commentary that something is wrong with his wiring. In 2014, he gave a presentation at Explorers Hall, at the National Geographic Society headquarters in Washington, D.C. The audience was there to hear from climbing photographer Jimmy Chin and veteran explorer Mark Synnott, but above all they had gathered to gasp at tales about Honnold.

Synnott got the biggest response from a story set in Oman, where the team had traveled by sailboat to visit the remote mountains of the Musandam Peninsula, which reaches like a skeletal hand into the mouth of the Persian Gulf. Coming upon an isolated village, they went ashore to mix with the locals. “At a certain point,” Synnott said, “these guys start yelling and they’re pointing up at the cliff. And we’re like, ‘What’s going on?’ And of course I’m thinking, ‘Well, I’m pretty sure I know.’ ”

Up came the photograph for the gasp from the crowd. There was Honnold, the same casual dude who was sitting on stage in a grey hoodie and khakis, now looking like a toy as he scaled a huge, bone-colored wall behind the town. (“The rock quality wasn’t the best,” Honnold said later.) He was alone and without a rope. Synnott summed up the villagers’ reaction: “Basically, they think Alex is a witch.”

When the Explorers Hall presentation concluded, the adventurers sat down to autograph posters. Three lines formed. In one of them, a neurobiologist waited to share a few words with Synnott about the part of the brain that triggers fear. The concerned scientist leaned in close, shot a glance toward Honnold, and said, “That kid’s amygdala isn’t firing.”

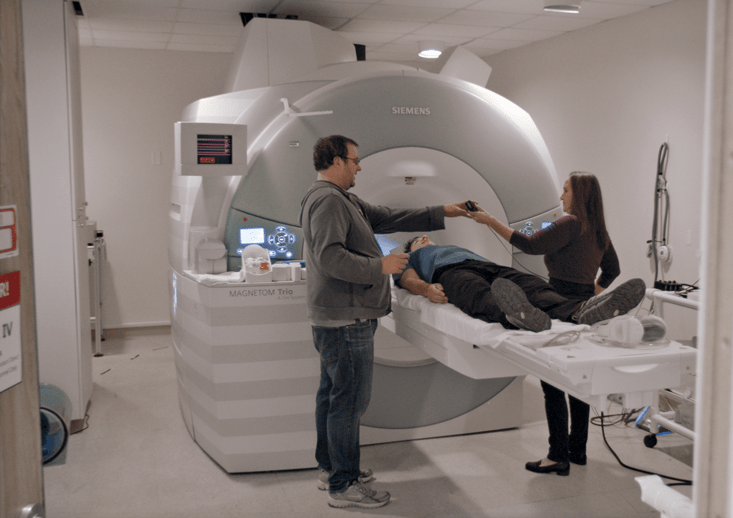

NO BIG DEAL: Technician James Purl and neuroscientist Jane E. Joseph put Honnold into an MRI tube to measure his brain’s fear levels. After looking at gruesome and arousing images inside, he commented, “I was like, whatever.”©2016 NGC Network International, LLC and NGC Network US, LLC

NO BIG DEAL: Technician James Purl and neuroscientist Jane E. Joseph put Honnold into an MRI tube to measure his brain’s fear levels. After looking at gruesome and arousing images inside, he commented, “I was like, whatever.”©2016 NGC Network International, LLC and NGC Network US, LLC

Once upon a time, Honnold tells me, he would have been afraid—his word, not mine—to have psychologists and scientists looking at his brain, probing his behavior, surveying his personality. “I’ve always preferred not to look inside the sausage,” he says. “Like, if it works, it works. Why ask questions about it? But now I feel like I’ve sort of stepped past that.”

And so, on this morning in March, 2016, he is laid out, sausage-roll style, inside a large, white tube at the Medical University of South Carolina, in Charleston. The tube is a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) brain scanner, essentially a huge magnet, which detects activity in the brain’s different regions by tracing blood flows.

Months earlier, I had approached Honnold about taking a look at his much admired, much maligned brain. “I feel totally normal, whatever that means,” he said. “It’d be interesting to see what the science says.”

“Why does he do this?”…

http://nautil.us/issue/61/coordinates/the-strange-brain-of-the-worlds-greatest-solo-climber-rp