In the “German Democratic Republic” they tell the story about a weary old man who tries to gain entrance into the Red Paradise. A Communist Archangel holds him up at the gate and severely cross-questions him:

“Where were you born?”

“In an ancient bishopric.”

“What was your citizenship?”

“Prussian.”

“Who was your father?”

“A wealthy lawyer.”

“What was your faith?”

“I converted to Christianity.”

“Not very good. Married? Who was your wife?”

“The daughter of an aristocratic Prussian officer and the sister of a Royal Prussian Minister of the Interior who persecuted the Socialists.”

“Awful. And where did you live mostly?”

“In London.”

“Hm, the colonialist capital of capitalism. Who was your best friend?”

“A manufacturer from the Ruhr Valley.”

“Did you like workers?”

“Not in the least. Kept them at arm’s length. Despised them.”

“What did you think about Jews?”

“I called them a money-crazy race and hoped that they would vanish from the Earth.”

“And what about the Slavs?”

“I despised the Russians.”

“You must be a fascist! You even dare to ask for admission to the Red Paradise — you must be crazy! By the way, what’s your name?”

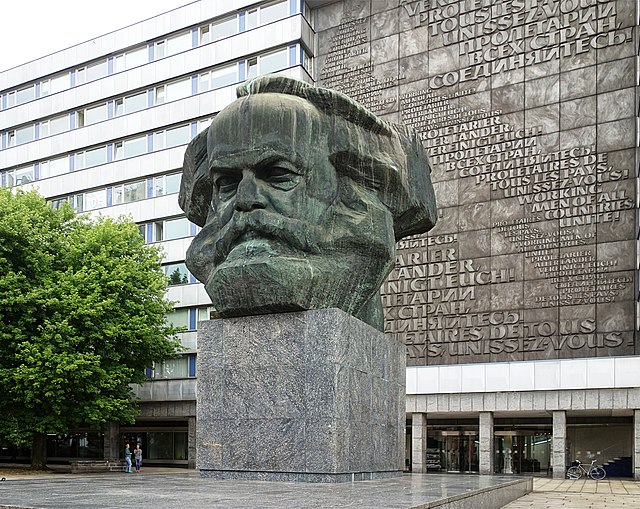

“Karl Marx.”

Man, indeed, is a very strange animal. This has been proved in many ways, but especially by the Marx-renaissance of recent decades. And yet the ideas of this odd and by no means constructive thinker are responsible all over the world for rivers of blood and oceans of tears. There can be no doubt that without the Communist challenge National Socialism, its competitor, would never have succeeded. Hitler boasted to Rauschning that he was the real executor of Marxism (though “minus its Jewish-Talmudic spirit”); thus the macabre death dance of our civilization in the past fifty years is due to that scurrilous, evil and unhappy man who spent half his life copying endless passages from books in the British Museum Library’s reading room. Yet, with the exception of numerous pamphlets and the first volume of a book, he left nothing but badly assembled, unpublishable manuscripts and a mountain of notes. It was his friend Friedrich Engels who, with the most laborious efforts, had to bring them into shape.

This Marx-renaissance is due largely, but not solely, to the rise of the New Left which argues that the dear old man had been thoroughly misunderstood by the barbaric Russians. Also a number of men and women would be horrified to be called Socialists or Communists but still have a soft spot in their hearts for a man who “at least was filled with compassion for the poor and was an admirable father and a tender husband.” Surely, Marx was a complex and contradictory person, and the renewed attention paid to him has produced a number of German books analyzing this most fatal figure of our times. Destructive ideas almost unavoidably derive from a destructive and — in this case — rather repulsive person.

Karl Marx was born in Trier, of Jewish parents, in 1818. Only a few years earlier this Catholic bishopric was forcibly incorporated into the Kingdom of Prussia and Karl Marx’s father embraced the Lutheran faith of the Prussian occupants. The children and the rather reluctant mother were baptized by a Prussian army chaplain only at a later date. The deism of Enlightenment was the true faith of Heinrich Marx who, however, was a cultured man and a devoted father. Young Karl finished high school-college with flying colors at the age of seventeen and set out to study law which he shortly abandoned for philosophy, eyeing the possibility of an academic career. He first matriculated in Bonn, then in Berlin where he fell under the spell of the Hegelians. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Jena, but renounced the idea of becoming a professor. He also gave up writing his self-centered poetry and his dream of running a theatrical review. He then married into the Prussian nobility and established himself as a free-lance writer in Paris where he soon clashed with the more humanitarian French socialists. He moved to Cologne, then returned to Paris and, finally —expelled from Belgium as an enemy of the established order — he took a permanent abode in London where, with interruptions, he remained until his death in 1883.

So much for the facts of his life. Within the last decade three books have been published in German analyzing Marx psychologically. These tomes are very different in scope but they hardly vary in their judgments. The authors belong to no “school” in particular, but all are serious students of our “hero’s” works and personal history. These books are Marx, by Werner Blumenberg, a small, but exceedingly readable paperback (1962), Karl Marx, Die Revolutionare Konf ession by Ernst Kux (1967) and Karl Marx, Eine Psychographie by Arnold Künzli (1966). The last two have not been published in the United States and whoever is acquainted with the tremendous difficulties encountered by translations of learned books in the United States will not be surprised. The reasons for this state of affairs are not solely of a financial nature. This article is partly based on the work of these authors…

more…

creativedestructionmedia.com/analysis/2021/07/23/portrait-of-an-evil-man-karl-marx/