To fully understand race and genetics, we have to consider where we came from and how we got here.

By: Stanley Fields and Mark Johnston

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved BiDil, a drug for the treatment of heart failure in self-identified black patients. . . . “Today’s approval of a drug to treat severe heart failure in [a] self-identified black population is a striking example of how a treatment can benefit some patients even if it does not help all patients,” said Dr. Robert Temple, FDA Associate Director of Medical Policy. “The information presented to the FDA clearly showed that blacks suffering from heart failure will now have an additional safe and effective option for treating their condition. In the future, we hope to discover characteristics that identify people of any race who might be helped by BiDil.”

—FDA News, June 23, 2005

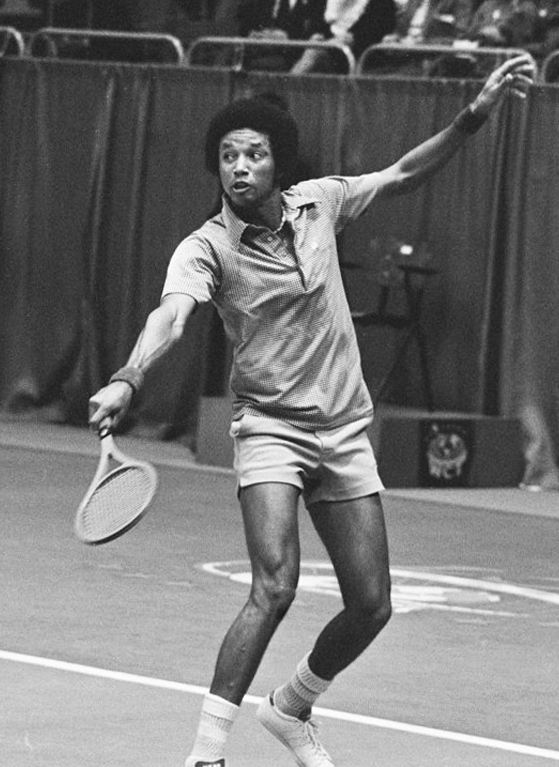

Top-seeded Jimmy Connors stepped onto Centre Court at Wimbledon for the 1975 men’s final having declared that it would be “just another day at the office.” Ranked number one in the world, the 22-year-old defending Wimbledon champion had not dropped a single set en route to the final. The brash left-hander was the overwhelming favorite against the other finalist, sixth-seeded Arthur Ashe. Connors was famed for his explosive outbursts on the court; the 31-year-old Ashe calmly closed his eyes and meditated between games.

The three previous times these rivals had met, Connors had prevailed decisively, and commentators at Wimbledon that day hoped only that Ashe would not be embarrassed on the court. To their surprise, Ashe began the match in dazzling fashion. Instead of trying to out-hit the hard-slugging Connors, Ashe brilliantly executed a game plan of slices, chip returns, lobs, and other change-of-pace shots, to dominate the first two sets 6–1.

Connors, never a quitter, fought back to win the third set 7–5, keeping alive his hopes for a stirring comeback. He started out the fourth set strongly to gain a 3–0 advantage and was but a point away from 4–1, but Ashe, resolutely sticking to his game plan even when on the defensive, rallied to win the set and match and become the first and still the only African American to win the Men’s Championship of the All England Club. It was the only time he would ever defeat Connors.

Four years after his triumph at Wimbledon, while participating in a tennis clinic, Ashe suffered a heart attack that necessitated quadruple bypass surgery four months later. It forced his retirement from tennis soon after, and his continuing heart problems led to more surgery in 1983.

Ashe never forgot his childhood in segregated Richmond, Virginia, where he had been excluded from whites-only tennis tournaments. Or the Davis Cup match in 1965 between the United States and Mexico that had to be moved from the private Dallas Country Club to a public facility because club members objected to his presence on their courts. He once said that if he was remembered only as a tennis player he would have been a failure. But he is remembered as so much more.

Few issues are as contentious in American society as race. As stellar a citizen of court and country as Ashe was, he was at one time called an Uncle Tom for appearing to legitimize the South African government. At other times he was criticized for not doing enough to further the careers of young black tennis players. Given the history of race in America, the relationship between race and genetics is a landmine for researchers who attempt to study the subject. A host of issues — the very definition of race, the dispute over whether race is a valid categorization of people, the question of which traits might have a race-specific genetic basis, the utility of using racial identity to assist in finding disease genes, and the value of targeting drugs to certain racial groups — provoke intense feelings and heated debate. Because humans seem to have a need to define and differentiate themselves, and because many Americans believe race is so evident a category since it seems to be plainly visible in front of their eyes, the use of race as a classifier of people pervades much of our collective daily existence…

more…

thereader.mitpress.mit.edu/around-the-world-in-50000-years-the-genetics-of-race/